“When a government official knocks on the door of a Uyghur person and says they should take a job far from home, the person knows this is not merely a request.”

Hi {{ First name | there }},

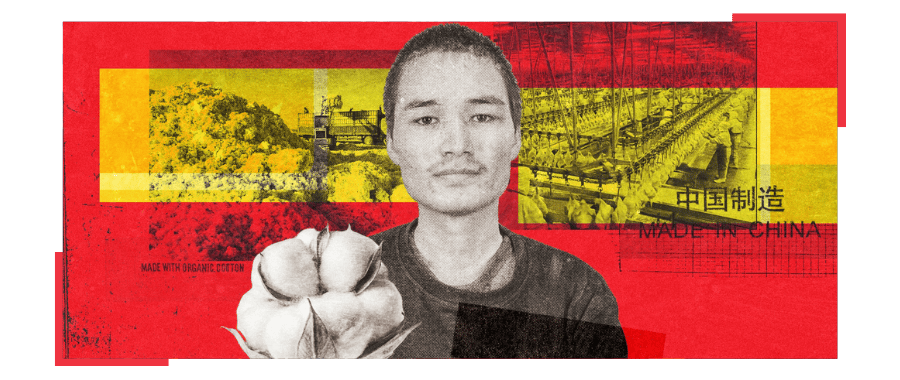

Four years ago, the US banned imports of cotton and cotton products from China’s western-most region, Xinjiang. Why? Because farming in the region involved widespread human rights abuses against Uyghurs and other ethnic minorities.

But there’s a worrying potential loophole to that rule. Cotton tracing focuses, quite reasonably, on the cotton, not the waste products of farming it – straw and seed. In fact, cottonseed meal is pretty useless – it contains a poison that makes it difficult to use as animal feed.

Or at least, it did. But then China made important breakthroughs in biotechnology that let them “turn waste into treasure”. And now, cottonseed harvested by forced labourers is being fed to animals across China – and ending up in the supply chains of brands like KFC and McDonald’s.

For China, this is hugely significant. The country depends on Brazil and the US for protein-rich feed; not ideal when you’re in competition as global superpowers. Producing its own feed makes China less reliant on imports.

For food producers like KFC and McDonald’s it’s more of a challenge. Our reporting shows that their outlets in China are selling chicken that has been reared on cotton seed linked to the coercive labour. Surprisingly, KFC didn’t respond to repeated efforts to get a comment. McDonald’s wouldn’t comment on the record.

The cottonseed industry is now billions of dollars worth of business, and also linked to pigs, cattle, seafood and other animals.

For people in the UK, there are more questions we need to think about. One of the food giants operating in China and linked to this trade supplies animal products to British supermarkets, including Tesco, Aldi and Sainsbury’s.

We don’t know if animal products on our supermarket shelves have been reared on Xinjiang cotton – although one retailer we approached said it wasn’t buying poultry from China at all. But it’s a risk that needs considering and efforts to screen animal feed for cotton will require significant investment.

Before I tell you more about this investigation, I wanted to thank our supporters. At TBIJ, we can only do ambitious journalism, which holds big corporations like McDonald’s and Tesla to account, with support from our readers. We also got a grant from the Pulitzer Center, a US non-profit which supports the best journalism.

This project took many months of reporting, editing and work on graphics and video. We had to bring in freelancers to help. And the legal review was another major cost for us. But that’s what it takes to do this kind of work. If you’re able to, we would love it if you could help us keep going by becoming a Bureau Insider.

Factchecked!

Each week we reveal a fascinating fact from our reporting…

Did you know?

Tax evasion is estimated to make up about £5.6bn of the UK’s tax gap – a number that significantly exceeds the budget allocated to the Met police each year.

Find out more

Each year, the UK’s tax authority collects less than what it estimates it should collect – which is known as the tax gap. Tax evasion is a deliberate attempt to cheat the revenue of tax owed and it made up about 14% of the tax gap, according to the latest figures.

But prosecutions of the enablers of tax evasion have plummeted by at least 75% in the past five years and are lower than previously claimed by HMRC.

Read more here.

How we tracked the workers shipped across China

Our series looking into Chinese forced labour was a classic piece of investigative journalism.

It started with a clue. Daniel Murphy, the indefatigable reporter who conceived of and led the project, saw a post on TikTok in late 2023. A Uyghur woman had put up a video of rain falling outside a factory gate somewhere.

Over the clip she posted a line from a song: “Why does the sky cry in the form of rain? My tears flow like a river.”

Daniel put his location-tracing skills to use and figured out that the video was filmed at a poultry plant thousands of miles away from Xinjiang, the Uyghur homeland. Instead, the woman was near the North Korean border.

This grain of information raised an important question. Daniel knew that the Chinese government had subjected Uyghurs to horrific human rights abuses for years. Thousands had been interned in labour camps, leading to a global outcry. But why was this woman so far from home?

Daniel dove in. He started looking for similar videos of Uyghurs and other ethnic minorities posting from factories in China’s eastern heartland. He found literally thousands. The workers weren’t directly raising the alarm – that would be far too risky. Usually they were sharing scenes from their daily life, working on the assembly line or having lunch. But often, they would include references to their hardship – poetic invocations of the bigger story of coercion.

Daniel geolocated the factories, using company names on the uniform or finding distinctive features on the buildings in the background to place them on a map. He also dug up hundreds of official government announcements and articles in state media, which corroborated that the factories received ethnic minority workers from Xinjiang via a government programme. In the end, we were able to identify and corroborate 75 factories fitting the bill.

And using trade records, we could establish that those factories supply at least 100 brands, most of them household names like Apple, Skechers or Crocs. I had the pleasure of emailing all of them and fielding their responses. Several of them were surprised at what we told them and promised to investigate immediately. Some questioned some of our information. Each response needed careful consideration and needed to be reflected appropriately in our stories.

We also partnered with The New York Times and Der Spiegel. They have top notch reporters in China who visited about two dozen of the factories we had identified. What they found confirmed our story and gave us more detail about what it was like for these people to be in a programme like it.

It was a huge effort, but very important work.

Breaking: Did coerced labour make your car?

Before you go, we’ve just published the latest revelation in our China series.

It exposes how thousands of ethnic minorities from Xinjiang have been pushed into forced labour schemes in China’s car industry.

Car Valley is an enormous industrial zone just outside Wuhan that has become an emerging front in China’s electric vehicle revolution. We linked at least 30 major car brands with workers brought in through this government programme, including in the valley and across eastern China. That includes everything from Mercedes, BMW and Ford to the EV heavyweights Tesla and BYD.

China’s car industry is in superdrive. Find out if your car brand is implicated – and how the companies responded.

What we’ve been reading

🔴 New documents show Big Oil offering sponsorships for everything from art to the Girl Scouts as part of a strategy to block climate change action desmog.com

🔴 RFK Jr may have antidepressants in his sights as he leads the US’s health policy. But debate over SSRIs has been raging for decades undark.org

🔴 Everyday Americans are setting up ‘laptop farms’, part of an intricate scam that lets North Koreans take remote jobs for US companies wsj.com

Thanks,

Franz

Franz Wild

Editor

ADVERTISEMENT

The Daily Newsletter for Intellectually Curious Readers

Join over 4 million Americans who start their day with 1440 – your daily digest for unbiased, fact-centric news. From politics to sports, we cover it all by analyzing over 100 sources. Our concise, 5-minute read lands in your inbox each morning at no cost. Experience news without the noise; let 1440 help you make up your own mind. Sign up now and invite your friends and family to be part of the informed.